What is "Merge Branches?"

Many users find the word "merge" to be confusing, since it seems to imply that we start out with two things and end up with only one. I'm not going to start trying to invent new vocabulary. Instead, let's just try to be clear about what we mean we speak about merging branches. I define "merge branches" like this:

To "merge branches" is to take some changes which were done to one branch and apply them to another branch.

Sounds easy, doesn't it? In practice, merging branches often is easy. But the edge cases can be really tricky.

Consider an example. Let's say that Joe has made a bunch of changes in $/branch and we want to apply those changes to $/trunk. At some point in the past, $/branch and $/trunk were the same, but they have since diverged. Joe has been making changes to $/branch while the rest of the team has continued making changes to $/trunk. Now it is time to bring Joe back into the team. We want to take all the changes Joe made to $/branch, no matter what those changes were, and we want to apply those changes to $/trunk, no matter what changes have been to $/trunk during Joe's exile.

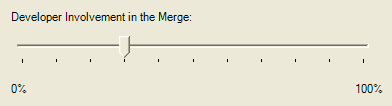

The central question about merge branches is the matter of how much help the source control tool can provide. Let's imagine that our SCM tool provided us with a slider control:

If we drag this slider all the way to the left, the source control tool does all the work, requiring no help at all from Joe. Speaking as a source control vendor, this is the ideal scenario that we strive for. Most of us don't make it. However, here at SourceGear we made the decision to build our source control product on the .NET Framework, which luckily has full support for the kind of technology needed to implement this. The code snippet below was pasted from our implementation of the Merge Branches feature in Vault:

public void MergeBranches(Folder origin, Folder target)

{

ArrayList changes = GetSelectedChanges(origin);

DeveloperIntention di = System.Magic.FigureOutWhatDeveloperWasTryingToDo(changes);

di.Apply(target);

}

Boy do I feel sorry for all those other source control vendors trying to implement Merge Branches without the DeveloperIntention class! And to think that so many people believe the .NET Framework is too large. Sheesh!

Best Practice: Take Responsibility for the Merge

Successfully using the branching and merging features of your source control tool is first a matter of attitude on the part of the developer. No matter how much help the source control tool provides, it is not as smart as you are. You are responsible for doing the merge. Think of the tool as a tool, not as a consultant.

OK, I lied. (Stop trying to add a reference to the System.Magic DLL. It doesn't exist.) The actual truth is that this slider can never be dragged all the way to the left.

If we drag the slider all the way to the right, we get a situation which is actually closer to reality. Joe does all the work and the source control tool is no help at all. In essence, Joe sits down with $/trunk and simply re-does the work he did in $/branch. The context is different, so the changes he makes this time may be very different from what he did before. But Joe is smart, and he can figure out The Right Thing to do.

In practice, we find ourselves somewhere between these two extremes. The source control tool cannot do magic, but it can usually help make the merge easier.

Since the developer must still take responsibility for the merge, things will go more smoothly if she understands what's really going on. So let's talk about how merge branches works. First I need to define a bit of terminology.

For the remainder of this chapter I will be using the words "origin" and "target" to refer to the two branches involved in a merge branches operation. The origin is the folder which contains the changes. The target is the folder to which we want those changes to be applied.

Note that my definition of merge branches is a one-way operation. We apply changes from the origin to the target. In my example above, $/branch is the origin and $/trunk is the target. That said, there is nothing which prevents me switching things around and applying changes in the opposite direction, with $/trunk as the origin and $/branch as the target, but that would simply be a separate merge branches operation.

Conceptually, a merge branches operation has four steps:

- Developer selects changes in the origin

- Source control tool applies some changes automatically to the target

- Developer reviews the results and resolves any conflicts

- Commit

Each of these steps is described a bit more in the following sections.

1. Selecting changes in the origin

When you begin a merge branches operation, you know which changes from the origin you want to be applied over in the target. Most of the time you want to be very specific about which changes from the origin are to be merged. This is usually evident in the conversation which preceded the merge:

- "Dan asked me to merge all the bug fixes from 3.0.5 into the main trunk."

- "Jeff said we need to merge the fix for bug 7620 from the trunk into the maintenance tree."

- "Ian's experimental rewrite of feature X is ready to be merged into the trunk."

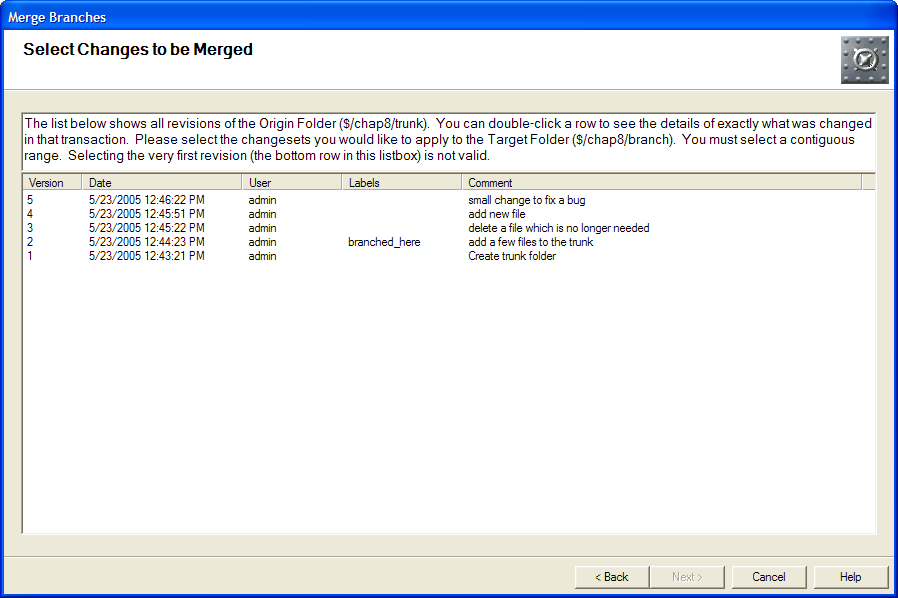

One way or another, you need to tell your source control tool which changes are involved in the merge. The interface for this operation can vary significantly depending on which tool you are using. The screen shot below is the point where the Merge Branches Wizard in Vault is asking me to specify which changes should be merged. I'm selecting everything back to the last build label:

2. Applying changes automatically to the target

After selecting the changes to be applied, it's time to try and make those changes happen in the target. It is important here to mention that merging branches requires us to consider every kind of change, not just the common case of edited files. We need to deal with renames, moves, deletes, additions, and whatever else the source control tool can handle.

I won't spell out every single case. Suffice it to say that each operation should be applied to the target in the way that Makes Sense. This won't succeed in every situation, but when it does, it is usually safe. Examples:

- If a file was edited in the origin and a file with the same relative path exists in the target, try to make the same edit to the target file. If this fails, signal a conflict and ask the user what to do.

- If a file was renamed in the origin, try doing the same rename in the target. Here again, if the rename isn't possible, signal a conflict and ask the user what to do. For example, the target file may have been deleted.

- If a file was added in the origin, add it to the target. If doing so would cause a name clash, signal a conflict and ask the user what to do.

- What happens if an edited file in the origin has been moved in the target to a different subfolder? Should we try to apply the edit? I'd say yes. If the automerge succeeds, there's a good chance it is safe.

Bottom line, a source control tool should do all the operations which seem certain to be safe. And even then, the user needs a chance to review everything before the merge is committed to the repository.

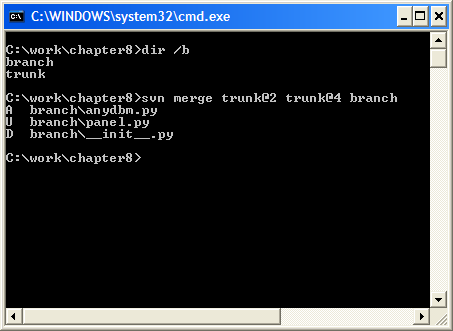

Let's consider a simple example from Subversion. I created a folder called trunk, added a few files, and then branched it. Then I made three changes to the trunk:

- Deleted __init__.py

- Modified panel.py

- Added a file called anydbm.py

Then I asked Subversion to merge all changes between version 2 and 4 of my trunk into my branch:

Subversion correctly detected all three of my changes and applied them to my working copy of the branch.

3. Developer review

Best Practice: Review the Merge Before you Commit

After your source control tool has done whatever it can do, it's your turn to finish the job. Any conflicts need to be resolved. Make sure the code still builds. Run the unit tests to make sure everything still works. Use a diff tool to review the changes.

Merging branches should always take place in a working folder. Your source control tool should give you a chance to do these checks before you commit the final results of a merge branches operation.

The final step in a merge branches operation is a review by the developer. The developer is ultimately responsible, and is the only one smart enough to declare that the merge is correct. So we need to make sure that the developer is given final approval before we commit the results of our merge to the repository.

This is the developer's opportunity to take care of anything which could not be done automatically by the source control tool in step 2. For example, suppose the tree contains a file which is in a binary format that cannot be automatically merged, and that this file has been modified in both the origin and the target. In this case, the developer will need to construct a version of this file which correctly incorporates both changed versions.

4. Commit

The very last step of a merge branches operation is to commit the results to the repository. Simplistically, this is a commit like any other. Ideally, it is more. The difference is whether or not the source control tool supports "merge history."

The Benefits of Merge History

Merge history contains special historical information about all merge branch operations. Each time you do use the merge branches feature, it remembers what happened. This allows us to handle two cases with a bit more finesse:

Repeated Merge

Frequently you want to merge from the same origin to the same target multiple times. Let's suppose you have a sub-team working in a private branch. Every few weeks you want to merge from the branch into the trunk. When it comes time to select the changes to be merged over, you only want to select the changes that haven't already been merged before. Wouldn't it be nice if the source control tool would just remember this for you?

Merge history allows this and makes things more convenient. The workaround is simply to use a label to mark the point of your last merge.

Merge in Both Directions

A similar case happens when you have two branches and you sometimes want to merge back and forth in both directions. For example:

- Create a branch

- Do some work in both the branch and the trunk

- Merge some changes from the branch to the trun

- Do some more work

- Merge some changes from the trunk to the branch

At step 5, when it comes time to select changes to be merged, you want the changes from step 3 to be ignored. There is no need to merge those changes from the trunk to the branch because the branch is where those changes came from in the first place! A source control tool with a smart implementation of merge history will know this.

Not all source control tools support merge history. A tool without merge history can still merge branches. It simply requires the developer to be more involved, to do more thinking.

In fact, I'll have to admit that at the time of this writing, my own favorite tool falls into this category. We're planning some major improvements to the merge branches feature for Vault 4.0, but as of version 3.x, Vault does not support merge history. Subversion doesn't either, as of version 1.1. Perforce is reported to have a good implementation of merge history, so we could say that its "slider" rests a bit further to the left.

Summary

I don't want this chapter to be a step-by-step guide to using any one particular source control tool, so I'm going to keep this discussion fairly high-level. Each tool implements the merging of branches a little differently.

For some additional information, I suggest you look at Version Control with Subversion, a book from O'Reilly. It is obviously Subversion-specific, but it contains a discussion of branching and merging which I think is pretty good.

The one thing all these tools have in common is the need for the developer to think. Take the time to understand exactly how the branching and merging features work in your source control tool.

Eric Sink is a software developer at SourceGearwho make source control (aka "version control", "SCM") tools for Windows developers. He founded the AbiWord project and was responsible for much of the original design and implementation. Prior to SourceGear, he was the Project Lead for the browser team at Spyglass (now OpenTV) who built the original versions of the browser you now know as "Internet Explorer". Eric received his B.S. in Computer Science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The title on Eric's business card says "Software Craftsman". You can Eric at